May is Mental Health Awareness Month, and in this post I’m going to unpack some beats/themes that can help writers portray mental illness authentically in their stories. I am not a medical professional, or an expert reader in this area—I don’t seek out books that tackle mental illness, and this post isn’t meant as a critique of any book or writer. That said, I do have experience living with bipolar, and I know a bit about storytelling. I hope you will find this post helpful as a writer’s tool, and motivational as you dive deeper into your characters’ mental health.

Story Beats to Consider

Living with mental illness is complicated. The following story paths are all valid opportunities to explore in your characters’ story arcs, or to build into their backstories and motivations. The following is a smorgasbord, hopefully rich with storytelling opportunities. Find what inspires you; don’t feel obligated to cover everything in a single story. Better to go deep with one or two themes than pay cheap lip service to an entire life.

1 – The Crisis

When you think about writing a story about mental illness, the first story beat that probably comes to mind is a severe, stressful crisis. For someone with bipolar, this could mean a months-long valley of depression, or a life-shattering manic episode; a hospitalization, or a suicide attempt. For a reader, these stories can be cathartic, eye-opening, and searing on the soul. Beyond the high-stress mental and emotional stakes, a crisis is ripe with trials for a family, professional life, and internal conflict; it is a natural tipping point. At the same time, a character enduring a mental health crisis may lose most of their agency. Be sensitive to the debilitating effects of an unbearable load. Dealing with feelings of guilt generated by a mental illness is one thing; constructing a narrative that blames an unwell character for their crisis is another.

It may be appropriate for the crisis event to be the entire focus of your story, especially if you’re writing a short story, or if the person suffering is a secondary character. However, if your main character suffers from a mental illness, you’re probably better off positioning the crisis as a central point in their arc, and developing other story beats around it. Too much focus on the crisis could make for a grating, unrealistic story.

2 – The Diagnosis

For me, finding out I had bipolar led to an identity crisis. I had known I was depressive for a few years, and been hospitalized once. After my big manic break, I wondered whether any pleasure I had ever experienced was real, or just a lie my mania had told me. Other people may experience relief when they receive their diagnosis. If they’re fortunate, they might have the benefit of an early intervention by a watchful professional, or a relative who knows the family’s mental health history. Or, as in my story, the initial diagnosis could be wrong.

Depending on your story’s historical context, a diagnosis could condemn your character, or be a balm. Consider the character’s worldview—whether they experience any relief from the jarring news may depend on their willingness or ability to accept the available treatment. I’m not just talking about asylums and castrations (real horrors of America’s not-so-distant past). Mental health treatment today, especially pharmacological, is largely trial and error. With a bit of luck, your psychiatrist and counselor are responsible, attentive experts. Most people who suffer from a mental illness today have awful stories of mismatched medications and wrongheaded therapists. The brain is still a mystery in many ways. Different areas of the States (and the world) have vast discrepancies in the availability of treatment. These complexities are ripe for exploration.

3 – Coming Out

With few exceptions, people who have a mental illness (especially a ‘really bad’ one) do not share their story beyond their closest friends and immediate family. I don’t think my wife’s extended family knew I had bipolar until a year ago. This is doubly true at work. Even in the safest, most caring professional environment, mental illness is not something most people want to bring up. As such, you’ll want significant build-up as your character convinces themselves they’re making the right decision; or, if it’s a spontaneous blurt-out, some self-reflection to indicate the weight or relief.

Consider this as a major inflection point for your character who has a mental illness. For me, the ‘Coming Out’ language of the LGBTQ community was helpful. Forgive me if I’ve misappropriated somehow; I needed language and had none. It is an emotionally charged conversation. Even if you trust and love the person who you’re opening up to with your whole heart, there is a sensation that you’re handing over the keys to your broken soul. The exposure is painful, even terrifying, because you are revealing an intimate story from your life that is likely loaded with trauma. Developed carefully, this is an opportunity for great healing in a story. (Or hurt, depending on how the listening party responds.)

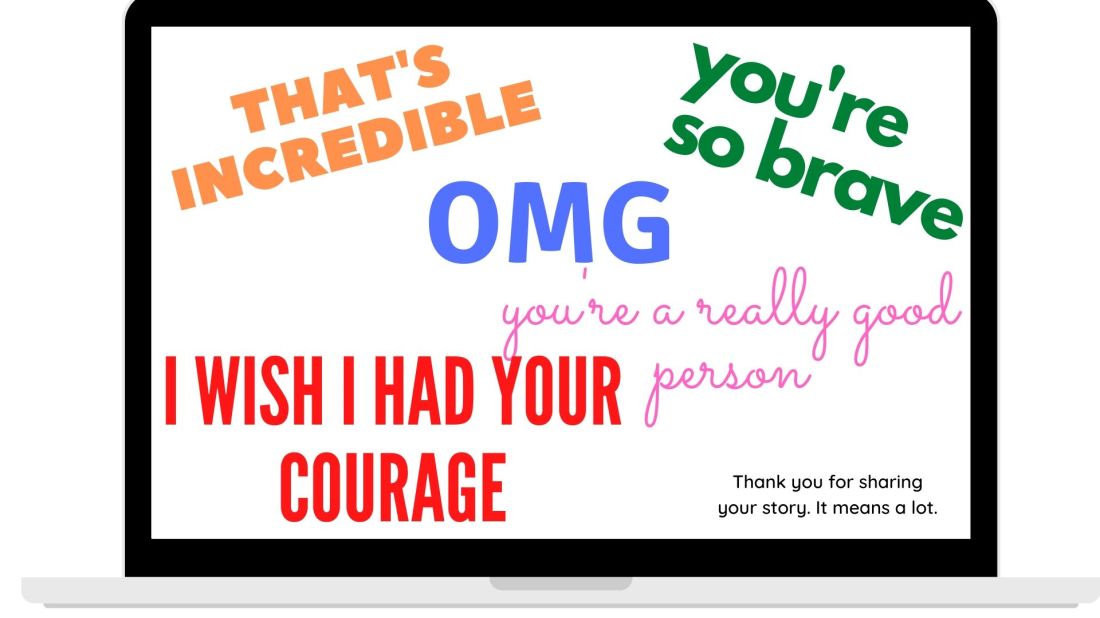

4 – The Sympathy

In my experience, exposing your mental illness to the public always ends with a half-dozen emails, each with the same response: ‘you are so brave’. It’s not a bad thing to say. There is an element of courage in sharing your traumatic truth. Reaching that point of sharing is a worthy arc for a character. However, I think this common theme is worth exploring for another reason: Is a compliment the best support to give someone for baring their pain? I’m not judging the compliment-giver. It is very hard to respond with empathetic love in these situations; in a way, responding can be just as personal and revealing as the ‘Coming Out’ itself.

Sympathy is supportive without offering further depth and commitment. And that’s fine. Only a handful of people have given me unadorned empathy and grace in response to my story; one of them is my wife. A similar relationship to develop in your story is the empathetic bond of a fellow traveler. After I tell my story, I usually hear from someone unexpected who needs to open up in a private, safe environment. This is a great blessing and can lead to a deep friendship.

I think one of the reasons that sympathy is worth exploring in a story is that a person suffering from a mental illness can easily take the compliments the wrong way. I did. Imagine a college student who publishes an op-ed about his depression. Suddenly, he is showered with praise by esteemed professors, popular young men, and attractive young women who had never given him the time of day. My hubris is showing. I believe there is a lesson here for writers: just as it’s dangerous to make mental illness your antagonist’s flaw, it’s also dangerous to make mental illness your protagonist’s heroic trait.

Sympathetic attention has a way of turning healthy self-esteem into unhealthy pride. The message sent may be ‘you’re brave [for sharing]’, but it’s very easy to hear ‘you became a hero by suffering and overcoming your depression’. Suffering is not a virtue, and coping with mental illness is not heroic; it’s as common and fundamental as brushing your teeth.

5 – Functioning/Coping

How does your character cope with their illness on a day-to-day basis? Do they take medicine? See a counselor? Do they have a helpful network of friends and family? What about their physical wellness? Are they into holistic approaches? Also, do they fail at coping? It’s possible to build a character whose central flaw affects their mental wellness, without making their illness a flaw in itself. For example, when I am lazy about exercising, my mental health suffers. My flaw (laziness) is intertwined with my mental health. It is a complex relationship worth exploring. At minimum, these are details you can include in your character descriptions. Shoot for authenticity with prescription dosages, symptoms, counseling styles, UV lamp wattages, and so on.

Consider too the most reviled mental health problems of our day. People who have a personality disorder, such as narcissism, psychopathy, or sociopathy, need to cope, too. If you’re writing genre fiction and have a nasty villain, be careful when you give them a mental illness. If your villain has a personality disorder, how did they gain and retain their power while living with a socially problematic illness? They must have coped, somehow. For a great example, watch The Sopranos.

6 – Recovery & Freedom

Some people who have a mental illness are fortunate enough to find treatments that allow them to lead relatively normal lives. For ten years I have functioned fairly well overall, and I haven’t been hospitalized. I count that as a tremendous blessing. Depression may come and go. When I am well, fear haunts me—fear that a medication will finally fail (changing meds is the worst), or I will suffer a devastating episode; and I have hope—hope that I won’t have to think twice about coping, that my mind will be blessedly clear, free from the tyranny of mania and the weight of depression.

Humans are remarkably adaptable. Most days, I don’t spend any time thinking about my bipolar, not even when I pop my pills morning and night. Thinking about my illness as an abstract concept for this blog post is not difficult. Developing new stories inspired by my illness is cathartic. I avoid dwelling on the memories of traumatic pain from my crisis, my diagnosis, and the times I failed to cope and did not function. Though, those stories do become less painful in the telling. If your character is healthy and well, consider what mental constructs they have designed to protect themselves and enjoy their lives.

— — —

That’s all for today. Hopefully, this has sparked some creative thoughts for you. As you can see, there are numerous stories to be told concerning mental illness, and even more ways to tackle each of those stories.

This post is not meant to be prescriptive or all-inclusive. It’s still important to flesh out your characters beyond their mental health. If you have follow-up questions that you’d rather ask in private, please find me on Facebook. Happy writing!

Very well written, Phil. Regarding this post, I love how you blended personal experience with literary endeavors. I lot of what you present here is “tip of the iceberg” but you share enough detail to encourage people to take some time, reflect, flush out ideas, and (especially) research when it comes to writing about mental illness or tacking one on to a character. Just like improv and character/relationship development — it’s not just about the mental illness but about the person, and focusing solely on that aspect is more of a flaw than the perceived mental illness itself.

Keep up the great writing, man!

LikeLike

Thanks, man. Appreciate the feedback. You know I wouldn’t be able to articulate this stuff clearly without our years together on the stage.

LikeLike

Lots of really great points made in this, not just writers but dealing with life in general. Thanks for sharing. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nyemade 🙂 Love to see everything you’re doing with mental wellness, too. Rock on 🙂

LikeLike